Plymouth, along with its sister port – Portsmouth, would be the recipient of the largest British construction project of the Nineteenth Century in the form of a ring of forts guarding the ports, and especially the naval bases, from attack. The scale of the project led to massive public expenditure and considerable work opportunities for decades before the fortifications were complete. The original plan stretched from Tregantle Fort in Cornwall around Plymouth and back down towards Fort Bovisand.

The reason for their construction was due to a mix of worries and concerns coming to the attention of Britain during the mid-Nineteenth Century. In particular, the Crimean War where the British and French, allied to defeat Russia, influenced military planners. The British and French landed on the Crimea in order to capture Sevastapol the main Russian port for its Black Sea fleet. Rather than assault Sevastapol directly from the sea, which was felt to be too difficult, an army was landed several miles away and marched to attack the port from the landward side. The idea was that if the Sevastapol was neutralised, the Russians would have no means to support a fleet on the Black Sea and so would be at the mercy of the British and French fleets. This is precisely what happened, only it took far longer than envisioned to complete, partially due to the extensive fortifications around the port itself. British strategic planners realised that the prime British ports on the South Coast were more than vulnerable to a similar kind of attack especially when it was realised that their defences had not been updated since the Napoleonic Wars some half a century earlier. Palmerston believed it was time for a serious upgrade of the ports’ defences.

Another factor was the changing nature of maritime technology and the fear that the Royal Navy was falling behind their near neighbours and historic rivals; the French. Steamships had already deprived Britain of one of its key lines of defence; the weather. Steamships could now sail against the wind in all but the severest weather conditions. This meant that the Channel was no longer the substantial barrier to invasion that it had proved in the past. Additionally, the French Navy were updating their steamships with iron plates; the so-called Ironclads. La Gloire was the world’s first ironclad steamship and was launched by the French in 1859 with another 9 ironclads on the production line. When Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited Cherbourg in 1858 they were quietly impressed by the modernisation efforts of the French Navy under the rule of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte – a name which in itself still had the power to concern the British. In addition to the new ironclads being constructed, they were also impressed to see the state of the defences of the French port and quietly noted that Plymouth and Portsmouth were nowhere near as effectively defended. In an era when the Royal Navy’s assets were stretched all around the globe, planners were concerned that her more old-fashioned ships might not be able to react quickly enough to a sudden strike from a modern navy just across the English Channel.

The British were also reminded of their vulnerability in a most brutal way by the Indian Mutiny in 1857 when sepoys rose up and turned on their officers and the Honourable East India Company. Officers, soldiers, civilians and most shockingly of all to the Victorians ‘ women and children’ were all targeted and many were slaughtered in an orgy of violence. What captured the public’s imagination was the fact that those who managed to survive the uprising did so largely thanks to defendable compounds and forts. Newspaper columns covered the heroic defences of Lucknow and Delhi or reported the slaughter at Cawnpore where the defenders negotiated to leave their defences. It was very clear in the public’s mind that more secure defences would have saved more lives. So, when there were discussions to build more fortifications in the late 1850s, it made perfect sense to large swathes of public opinion to take sensible precautions.

Another factor that made the building of the forts more palatable was the deteriorating political and diplomatic relations with France. In 1858 Louis Napoleon came close to being assassinated by an Italian nationalist called Felice Orsini. The attempt only narrowly missed and killed 8 bystanders and wounded 156 more. There was an outcry in France when it was realised that Orsini and his fellow plotters had been based in England and had been granted political asylum there also. There was further outrage when it was proved that the explosives had been made in England and had been smuggled to Paris with the help of English sympathisers. Within days of these revelations, a group of French officers stationed along the Channel announced that they would happily invade England if given permission to do so. These comments were amplified by the French press which goaded the English press into similarly jingoistic responses. The alliance of just a few years earlier seemed to lie in tatters. Attempts by Palmerston and Louis-Napoleon to patch up their differences led to demands for Palmerston to resign as PM for not standing up to the French. It was clear that reconciliation was not a public priority and that anti-French fears helped provide the environment that led to the construction of the forts.

It should also be remembered that the mid-Nineteenth Century saw British engineering confidence and financial strength at an all-time high. Britain had the engineering talent and financial muscle required to pay to defend the homes of Britain’s most important imperial asset; the Royal Navy. It was the Royal Navy that kept the trade routes open and projected British power on a truly global scale. It made perfect sense to ensure that the home ports could never be threatened. The very fact of the existence of these fortifications were to ensure that no power even considered attacking the ports.

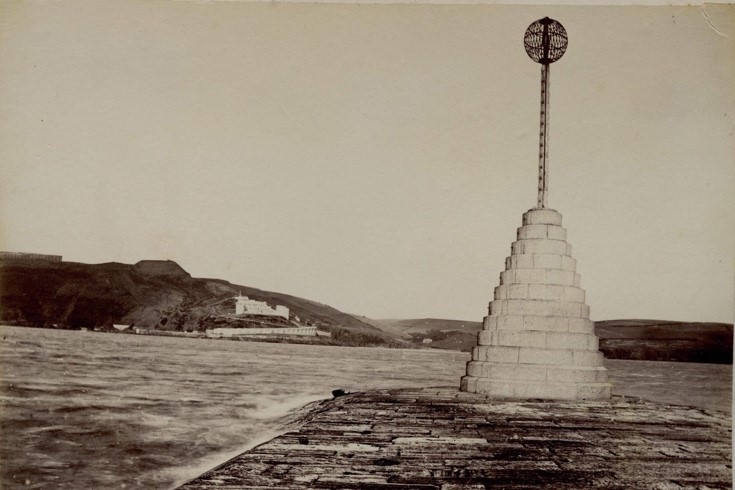

A Royal Commission was established in 1859 to consider the defences of Britain’s ports and it was to no-one’s surprise that they recommended a huge investment in upgrading the clearly inadequate facilities of Plymouth and Portsmouth. The building work in Plymouth started in earnest in 1860 after the passing of a Defence Act which made funds available for the ring of forts that were to guard the city from attack from any direction. Hence, there were also sea-facing defences. These included the construction of a fort next to the Breakwater and forts on either side of Plymouth Sound and further fortifications on Drake’s Island to guard against a seaborne invasion. The existing Citadel was integrated into the coastline defences. A line of fortifications centred on Crownhill Fort was to ensure that no landward attempt to seize the port could be attempted. Forts were also placed on the Rame Peninsular in Cornwall and as far west as Tregantle overlooking the likeliest landing beaches at Whitsands for any attempt to seize Plymouth quickly. The entire city was to be cocooned. Firing lines were sighted from all the forts which had overlapping zones of fire and they were connected by a covered military road behind them. Each of the forts was given a substantial budget to garrison and house the soldiers necessary for the defence of the port. Starting from the furthest East and travelling in a clockwise direction the forts were: Tregantle, Scraesdon, Ernesettle, Agaton, Woodlands, Crownhill, Bowden, Eggbuckland, Austin, Efford, Stamford, Staddon, and Bovisand. Picklecombe Fort and the Breakwater Fort were to add protection to the seaward approaches to the Hamoaze. There were also many batteries covering various approaches. Fort Bovisand’s position was to both cover the Eastern entrance to the Sound and the Breakwater and also as it had an existing harbour that had been constructed by John Rennie when he was overseeing the building of the Breakwater. This landing point would either have to be destroyed or incorporated in to the defences. Hence Fort Bovisand was placed down on the waterline.

The design was largely undertaken by Captain Edmund Du Cane of the Royal Engineers. The great advances in military technology enabled him to break from the centuries old practice of continuous line defences. Each of the forts was designed as a polygon surrounded by a ditch which itself was protected by caponiers (powerful, casemated structures which provided flanking fire across ditches). Guns, sometimes in casemates, lined the tops of the ramparts and the barrack blocks within were made bomb-proof by the use of mounded earth.

The outbreak of the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865 seemed to confirm the wisdom of Britain’s precautions, especially as it started with an initial onslaught on Fort Sumter. The new firepower unleashed in the war seemed to confirm that only modern construction techniques were resilient enough to defend against the latest generation of artillery and munitions.

However, it was a war that began in 1870 that reduced the fortifications’ military rationale. The Franco-Prussian war unleashed a new and more mobile form of war based on the ability of train lines to move large numbers of troops quickly and efficiently. The shattering defeat of France in that war also removed her as the pre-eminent threat on the continent. She was to be replaced in that role by the newly created Germany.

Germany was developing a continental power with little naval capability available, at least until the Tirpitz Plan of the 1890s. Plymouth’s considerable defences were no longer as vital following this Franco-Prussian war, just as they were reaching completion. Individual forts had been completed in the 1860s but the integrated whole was not finished until 1872, by which time they were already being regarded as expensive defensive luxuries. Evidence of this downgrading was revealed in the early 1880s when many of the guns from the forts were moved to the Far East colony of Hong Kong. They were actually moved there as something of a compromise when the military planners and government officials there fell out over the costs involved in updating the defences of such a remote colony. Lord Derby, the Colonial Secretary, personally intervened to solve the deadlock by proposing using some of the guns from Plymouth. This was no theoretical threat to Hong Kong’s defence as within months of the guns arriving France declared war on China and the guns were seen as a key component at keeping the French Navy in particular at arm’s length. It is interesting that the Palmerston’s forts were built to defend the city from France and that some of these very same guns were sent to the Far East for exactly that reason! It is perhaps no surprise that from around this time that the term “Palmerston’s Follies” began to come into circulation. Palmerston was associated by most commentators as having been the prime mover for their construction.

Despite this downgrading, the 1880s and 1890s saw further additions to the defences primarily around Plymouth Sound. This period in imperial history was referred to as the period of Splendid Isolation when Britain had no obvious allies and many potential enemies. Advances in shipping and gunnery, especially in terms of ranges, also motivated defensive planners to add yet more guns and batteries such as at Penlee Point with guns that could fire seriously long distances out to sea. Whitsand Bay Battery added yet more guns to cover the impressive beaches at Whitsand and prevent any enemy ships from anchoring there and bombarding Devonport Dockyard over the Rame Peninsular. Grenville Battery did something similar covering Cawsand Bay.

Despite this downgrading, the 1880s and 1890s did see further additions to the defences primarily around Plymouth Sound. This period in imperial history was referred to as the period of Splendid Isolation when Britain had no obvious allies and many potential enemies. Advances in shipping and gunnery, especially in terms of ranges, also motivated defensive planners to add yet more guns and batteries such as at Penlee Point with guns that could fire seriously long distances out to sea. Whitsand Bay Battery added yet more guns to cover the impressive beaches at Whitsand and prevent any enemy ships from anchoring there and bombarding Devonport Dockyard over the Rame Peninsular. Grenville Battery did something similar covering Cawsand Bay.

The new century brought new threats as guns could fire further and more accurately, submarines started appearing and torpedoes could also be fired from fast moving launches and small ships. The casemates in the forts were designed for long term duels with armoured ships and would allow the gunners to reload muzzle loading guns in comparative safety. However, as gun technology improved markedly quick firing breach loading guns became more available. However, their very speed of firing generated far more smoke than the enclosed fortifications could disperse. One such solution was to add more gun emplacements to the approaches. Hence, the Renney and Lentney Batteries were constructed from 1905 out past Bovisand which had hitherto anchored the Eastern part of Plymouth’s defences. The two world wars would show the versatility of these emplacements as the guns could be changed according to the threat.

A new lease of life was found for the fortifications in the First World War as defences were required to ensure that shipping and troopships could enter and leave the safety of the harbour. The fortifications provided valuable barrack and training space for British and Imperial units coming into the city before being sent out to other theatres of war, to France or elsewhere. Crownhill Fort, for instance, was used as a transit fort for troops being sent to the Turkish and African fronts. For example it was a staging area for troops being sent to the Gallipoli Peninsular in 1915.

The Second World War also saw the forts prove their utility and were upgraded and fully manned in the expectation of an invasion in 1940 and 1941. As this threat subsided, the platforms and forts provided excellently defended positions for anti-aircraft guns, barrage balloons and searchlight emplacements. The reinforced concrete and iron designs helped protect the city’s defenders from high explosive bombs and were unfazed by incendiary devices. Bovisand Fort was hit directly by two bombs from German aircraft only for them to do no damage whatsoever. Their deep magazines added further protection and utility to the defending forces. Crownhill Fort was designated the headquarters of Plymouth Command and co-ordinated the anti-aircraft and civil defence measures from the relative safety of its formidable walls and embankments. Many of the forts were set aside for accommodation for American units in the build up to the D-Day landings.

It was not until 1956 that the gun batteries were dismantled – this was when Fort Bovisand was abandoned by the Ministry of Defence. Parts of the defences were still used up until the Falklands War. 59 Commando Engineers were based at Crownhill Fort until the 1980s. They even built a Nordic ski route around the perimeter to practice their role in supporting NATO in the Arctic Circle. The army gave up its control of Crownhill Fort as late as 1986. Many of the pre-fab buildings that still exist surrounding the fort used to be the extended barracks. Tregantle and Scraesdon Forts are still used by the Royal Marines for training purposes. Fort Bovisand became a diving school and outdoor activity centre from 1970 until the beginning of this century. It is currently being refurbished into housing and leisure facilities.

Stephen Luscombe

December 2021