CAWSAND BAY

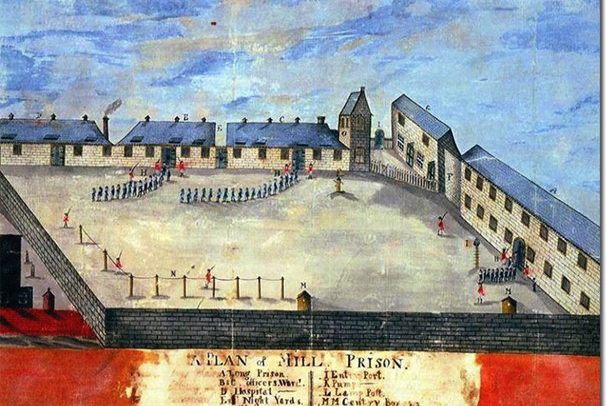

Gazing out over the Breakwater from Bovisand you can see Cawsand Bay. It looks very tranquil and beautiful but just over two centuries ago two momentous events occurred in that sheltered bay. Many people know that the Spanish Armada sailed past Plymouth Sound in 1588 only to meet its doom further up the English Channel at Gravelines. Few people realise that in 1779 an equally impressive multinational enemy fleet carrying tens of thousands of enemy soldiers anchored in Cawsand Bay. This 60 ship fleet was fully intent in putting ashore 30,000 French and Spanish soldiers to attack what was then called Plymouth Dock (what we now call Devonport). This fleet arrived as part of the wider American War of Independence which had begun in earnest in 1776. As the British mishandled early events, both Spain and France were encouraged to join the war against their historic foe and take advantage of Britain’s strategic and military difficulties. In many ways the war escalated in to a world war with American, French and Spanish attacking British shipping all over the world and colonies such as those in the Caribbean, India and Gibraltar amongst others. The planned attack on Plymouth was part of this escalation of the war. It is believed that they were working on intelligence gathered by a spy who went by the name of Comtes de Parades. He seems to have spent a great deal of time, money and effort in Plymouth gathering information about Plymouth Dock, the Citadel and the surrounding defences. He appears to have bribed a sergeant in the Citadel to gain schematics of its layout and he had entered the dockyards frequently claiming to be a legitimate trader in maritime equipment seeking to supply the Royal Navy. The plan was to send the ships up the River Tamar to capture the various prison hulks and then put troops ashore to capture Mill Prison (near the Duke of Cornwall Hotel) and release the American Prisoners of War being held there to add to their own forces. These forces would then attack Plymouth Dock from the landward side whilst being bombarded from the River Tamar. The soldiers and prisoners would then board the ships and escape.

Seeing an enemy fleet sail in to Cawsand Harbour alarmed officials and local people alike. Hurriedly, cannons were dragged into position, booms were placed across the Tamar and the Cattewater and Prisoners of War were taken off their hulks and marched into the interior where they would pose less threat. As fortune would have it, a severe storm on August 21st caused havoc with the enemy fleet. Unfamiliar with the depths and tides, the fleet dispersed back into the Channel rather than run aground or in to one another. Further fortune favoured the British when a returning flotilla of Royal Naval ships under the command Sir Charles Hardy hove into sight of the Rame Peninsular. In fact, they had been out searching for the invasion fleet but had missed it totally. As the Royal Naval ships readied for action, the larger but more cumbersome troopships of the Franco-Spanish fleet broke off and sailed home without firing a shot.

The authorities were greatly relieved but the affair convinced them of the need to redouble efforts to fortify and improve the defences around Plymouth Dock and the Sound in general. A new blockhouse was built at Higher Stoke to cover the landward entrance to Plymouth Dock. Further gun battery emplacements were built around the Hoe including at Mount Edgcumbe overlooking Cawsand Bay! Additionally a new barracks was built for the Royal Marines at Stonehouse where they are still housed to this day. Memories of the threat to release prisoners would be rekindled just a couple decades later when Britain started fighting the French again in the Revolutionary and French Wars. Remembering the 1779 threat, they took the decision to build a prison on Dartmoor at Princetown to house Prisoners of War rather than leave them on hulks along the Tamar to be freed and used by any attackers or invaders.

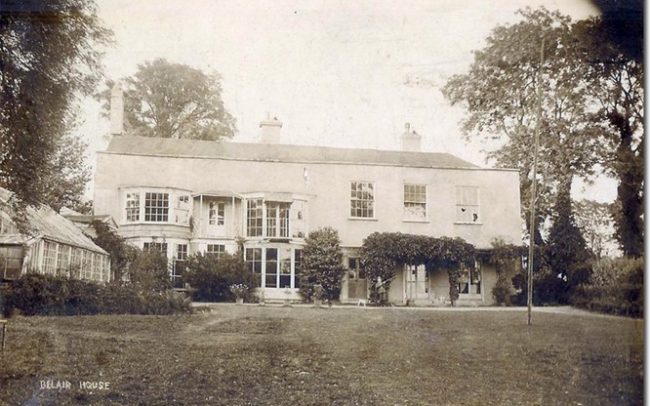

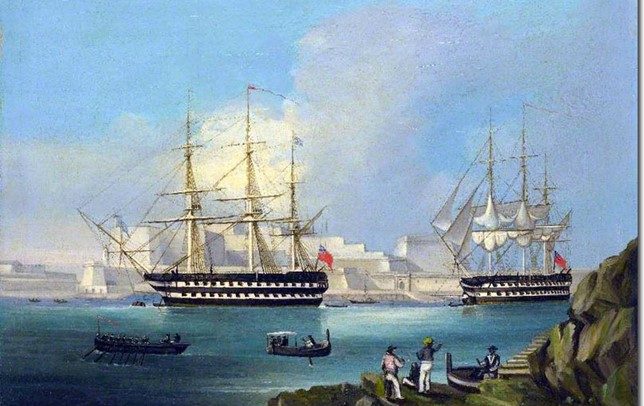

Fortunately for Plymouth, there was no equivalent threat of an attack on Plymouth during the Napoleonic Wars, but there would still be a very important prisoner brought to Cawsand Bay in 1815. No less a man than Napoleon himself. After the battle of Waterloo, Napoleon Bonaparte surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of the Bellerophon in the hope that he would be treated more fairly by the Royal Navy than he might have expected from the Royalist French. Maitland returned to Plymouth with his unusual passenger to await further orders on what to do with him. Napoleon was deliberately kept from coming ashore at Plymouth otherwise he might be afforded the rights of the Magna Carta and demand a trial. There was little appetite for such an event that might drag on for years, cost a fortune and worst of all he may have found sympathisers in the jury and in the court of public opinion. If he remained on board ship anchored out at sea off Cawsand then he would come under the Admiralty Law of the Royal Navy. In effect he could be treated as a Prisoner of War. Key Royal Naval senior officers met at Belair House in Pennycross to weigh up the options and to discuss what to do with their prisoner.

Belair House belonged to Captain Thomas Elphinstone who was a kinsman of Lord George Keith Elphinstone who was the Admiral of the Channel Fleet and Lieutenant Governor of Plymouth. Also present was Captain Maitland and Admiral Sir Thomas Duckworth the Commander-in-Chief in Plymouth. The Admiralty sent messages to Belair House seeking Lord Keith’s recommendations. The Admiralty was concerned at the notoriety of Napoleon and that revolutionary sympathisers might start arriving in Plymouth from all over the country. They wanted a quick and decisive solution. Apparently, in Belair House they cleared the dining room table of plates and dishes and laid out maps and considered the pros and cons of various locations that the Royal Navy could access easily across the globe. Thomas’ younger nephew Alexander Elphinstone stood guard with a drawn sword at the door to the dining room to make sure nobody could eavesdrop on the discussions.

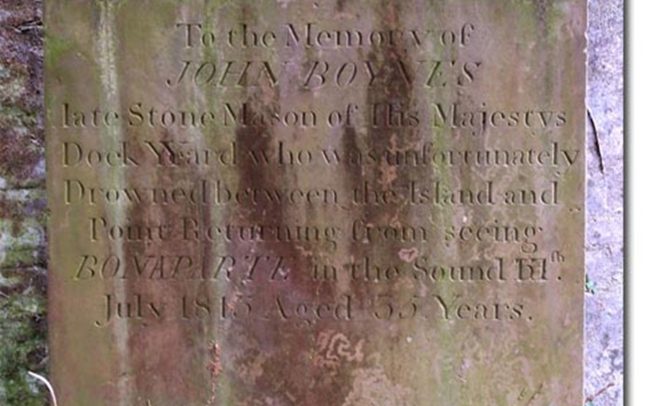

It should be said that whilst awaiting his fate Napoleon became quite the tourist attraction as people came from miles around to catch a glimpse of the renowned warrior and would-be Emperor on his own personal prison ship. He generally left his cabin to walk around the deck of the ship every evening at 6pm. There could be quite a commotion as people paid boatmen to take them out to see him at that time. Several times, blank shots had to be fired out over the water to keep sightseers at bay. There is a famous painting in Plymouth Museum which shows the extent of the mayhem. It reached such a point of pandemonium that at least one person, John Boynes, was killed in an accident whilst attempting to view the Great Man. His gravestone marking the events surrounding his death can be seen in the graveyard of St Andrew and St Luke at Stoke Damerel.

Napoleon was also intrigued to see the construction of Plymouth’s Breakwater which had commenced in 1812 and largely to benefit the ships of the Royal Navy. Much to the satisfaction of the architect John Rennie, Napoleon was said to have admired the scale, extent and ambition of the project. He is reported to have said that only after seeing the extent of this construction project could he understand how France could have lost a war to a country like Britain.

The officers gathered at Belair House eventually hit on the idea of the remote Atlantic island of St. Helena as Napoleon’s destination and prison. Once cleared with the Admiralty, Napoleon’s fate was kept a secret until Lord Keith boarded the Bellerophon to inform Napoleon directly. Napoleon was horrified and regarded the sentence as an effective death penalty. He attempted to negotiate and argue with Lord Keith who doggedly failed to engage and merely kept repeating that he was following orders of the Admiralty and would ensure that they were undertaken in full. The ship set sail before anyone could divulge their new mission. They did not want anyone to know of the destination in case an attempt to intercept Napoleon was made. Napoleon never did set food on British soil despite his years fighting against this country. According to Captain Maitland, as Napoleon saw the Rame Peninsular recede behind him, he commented “Enfin, ce beau pays” (at the end of the day, it is a beautiful country)

So, gazing out to Cawsand Bay try to envision the sight of these two events in 1779 and in 1815. First of the invasion fleet full of soldiers ready to sack a key naval port just around the corner from where they lay – within range of some of their cannons even. Secondly, the French Emperor who stood proudly upon the Bellerophon as tens of thousands of sightseers desperately tried to catch a glimpse of the famous man before he disappeared in to oblivion. Had you been stood at Bovisand you would have had ringside seats of these remarkable events.

Stephen Luscombe